You’ll often be the first to notice subtle changes when your fluid balance falters. Thirst, dry sticky mouth, reduced or dark urine, dizziness with standing, rapid heartbeat, low blood pressure, poor skin turgor, and slowed thinking are common, especially in older adults, infants, and people on diuretics. Know practical signs and thresholds for action, and when to get urgent help.

Early Warning Signs to Watch for

When you lose more fluid than you take in, early clinical signs appear and can be recognized: thirst, dry mouth, reduced urine output with darker urine, and decreased skin turgor. You should monitor urine frequency and color—oliguria and concentrated urine indicate reduced circulating volume. You’ll often note tachycardia and orthostatic blood pressure changes; measure heart rate and standing and supine pressures to quantify volume deficit. You may feel lightheaded, fatigued, or cognitively slowed; those symptoms reflect reduced cerebral perfusion. Skin turgor assessment and capillary refill provide rapid bedside data, though age alters accuracy. Implement prompt oral rehydration when appropriate and escalate to intravenous therapy based on hemodynamics, ongoing losses, and comorbidities. Use objective metrics and serial reassessments to guide innovative, evidence-based interventions in practice.

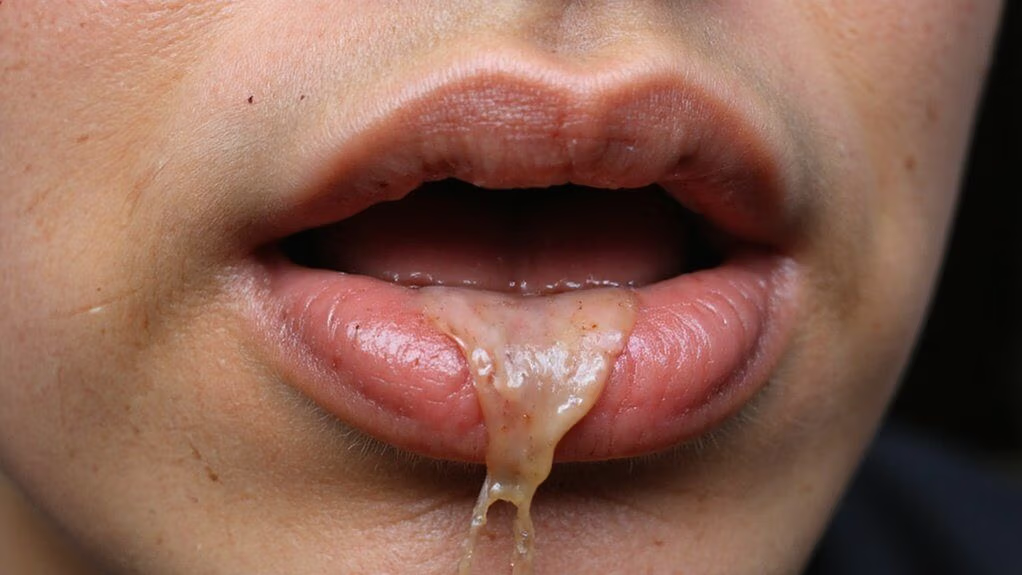

Dry Mouth and Sticky Saliva

What does dry mouth and sticky saliva tell you about hydration status? You produce less saliva when extracellular volume falls; mucosal surfaces feel dry and saliva becomes viscous. These are early peripheral markers of reduced intake or increased loss. Assess frequency, duration, and context; correlate with heart rate, dizziness, and oral mucosa appearance. Interventions include measured fluid replacement and monitoring output and vitals; consider medical review if persistent.

| Sign | Mechanism | Clinical action |

|---|---|---|

| Dry tongue | Reduced salivary flow | Rehydrate, reassess |

| Sticky saliva | Increased viscosity | Encourage sips, reassess |

| Parched feeling | Mucosal desiccation | Monitor trends, document |

| Nocturnal dryness | Overnight hypovolemia | Evaluate intake timing |

Act early.

Dark, Concentrated Urine and Decreased Output

If your urine turns dark and volume falls, the kidneys are conserving water—driven mainly by increased vasopressin release and reduced intake or ongoing fluid losses. You’ll notice higher specific gravity and concentrated metabolites; urine color and frequency are practical, validated markers of hydration status. Measure output and monitor trends rather than single readings. Address causes: increase sensible fluids, replace electrolytes when losses are significant, and evaluate diuretics or endocrine contributors if output remains low. Seek prompt evaluation for oliguria (<0.5 mL/kg/h) or sudden reduction. Innovative monitoring tools (smart cups, wearable sensors) can augment self-assessment. Document medication and illness triggers to inform interventions promptly.

- Check color and frequency daily.

- Record volume trends quantitatively.

- Escalate care for persistent low output or dark urine.

Dizziness and Lightheadedness

Because reduced intravascular volume lowers cerebral perfusion, you’ll often feel dizziness or lightheadedness when dehydrated; these symptoms commonly reflect hypovolemia and orthostatic hypotension rather than primary vestibular disease. You may notice transient visual blurring, presyncope on standing, tachycardia, and weakness. Evaluate orthostatic physiologic signs and monitor urine output; treat with guided oral or IV rehydration and reassess perfusion. Use innovative monitoring (wearables, continuous BP) when available to detect early decline. Avoid unnecessary vestibular testing unless symptoms persist after volume correction.

| Finding | Clinical implication |

|---|---|

| Orthostatic BP drop | Suggests volume loss |

| Tachycardia | Compensatory hypovolemia |

| Presyncope | Risk of syncope |

| Rapid improvement with fluids | Confirms volume-related cause |

Document trends and adjust therapy; prioritize rapid restoration of intravascular volume to reduce morbidity and enable safe recovery and monitor outcomes.

Headaches and Trouble Concentrating

You may develop headaches and impaired concentration when you’re dehydrated. Even modest fluid loss reduces brain volume and alters cerebral blood flow and electrolyte balance, which can trigger pain receptors and slow cognitive processing. Restoring fluids and electrolytes often improves attention and decreases headache intensity within hours, so rehydration is a first-line, evidence-based intervention.

Why Dehydration Causes Headaches

When total body water falls, brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid volume decrease slightly, which can pull on pain-sensitive meninges and stretch surrounding blood vessels, provoking headache. You’ll also experience systemic effects: reduced plasma volume raises blood viscosity, altering cerebral perfusion and triggering nociceptors. Osmolality increases shift intracellular-extracellular fluid balance, activating trigeminal pain pathways. Neurochemical changes—lowered serotonin and altered ion channels—can sensitize pain circuits. Clinical studies correlate mild dehydration with increased headache frequency and intensity, though individual thresholds vary. Monitor intake and symptoms; early intervention mitigates progression. Consider targeted rehydration strategies guided by symptoms and hemodynamic signs.

- Meningeal traction and vascular stretch

- Increased blood viscosity and perfusion changes

- Osmotic shifts activating trigeminal nociceptors

Assess risk factors and document response to rehydration treatment.

Improving Focus With Hydration

Mild dehydration impairs attention and working memory through the same hemodynamic, osmotic, and neurochemical mechanisms that provoke headaches. You can restore cognitive performance by rehydrating promptly; randomized trials show modest improvements in reaction time, vigilance, and short-term memory after fluid replacement. Aim for regular, small-volume intake (150–250 mL every 15–20 minutes during cognitive tasks) and monitor urine color and frequency as objective proxies. For extended sessions, include electrolytes to maintain plasma osmolality and avoid free-water overload. Avoid excessive caffeine diuresis; plan intake to balance alertness and fluid status. Implement simple sensors or scheduled reminders to quantify fluid adherence and link intake to task performance. These strategies translate physiological principles into operational tools that improve focus reliably. You should measure outcomes to validate improvements objectively.

Fatigue, Weakness, and Irritability

Although often overlooked, fatigue, weakness, and irritability are common early signs of dehydration, caused by reduced plasma volume and altered electrolyte balance, and don’t require large fluid losses to occur—1–2% body-mass water loss can impair cognition and physical performance, making it harder to concentrate, sustain activity, or regulate mood. You may notice slower reaction times, muscle tiredness, and reduced motivation; these reflect lower cerebral perfusion and disrupted sodium/potassium gradients. Early recognition lets you intervene with measured fluid and electrolyte replacement before function declines.

- Short attention span and mental fog

- Decreased muscular endurance and perceived effort

- Heightened irritability and mood variability

Monitor intake relative to activity and environment; target modest, evidence-based rehydration to restore function. If symptoms persist, consult a clinician for tailored fluid strategy.

Reduced Sweating and Cool, Clammy Skin

Because plasma volume falls and sympathetic vasoconstriction increases, eccrine sweat production decreases and the skin can feel cool and clammy, a clinical sign of hypovolemia and impaired thermoregulation. You may notice diminished sweating during exertion or heat exposure; this indicates reduced cutaneous perfusion and sympathetic-mediated sweat gland suppression. Assess for accompanying tachycardia, hypotension, orthostatic changes and altered mental status to corroborate systemic volume deficit. Use objective measures—continuous core temperature, skin conductance, and noninvasive hemodynamic monitoring—to quantify dysfunction and guide targeted fluid resuscitation. Early intervention restores thermoregulatory capacity and reduces risk of heat injury. In research and product development, integrate wearable sweat sensors and real-time analytics to detect these physiologic shifts before clinical deterioration. You should document findings, escalate care, and notify clinicians without delay.

Poor Skin Elasticity and Dry Skin

When you assess skin turgor and moisture, poor elasticity and dry skin point to extracellular volume loss and impaired interstitial hydration. You’ll notice delayed recoil when pinched, matte, rough surface texture, and decreased turgor at dependent sites; these are reproducible, measurable signs correlating with mild-to-moderate dehydration. Quantify with simple bedside tests and document serial changes to guide fluid management and innovation in monitoring. Consider objective adjuncts like bedside ultrasound or hydration biomarkers in research settings. Practical steps include:

- Perform a standardized turgor test at the forearm or sternum.

- Record moisture, texture, and recoil time in the chart.

- Use serial observations to evaluate response to rehydration.

You should integrate these findings into a structured assessment protocol. It informs targeted rehydration strategies clinically.

Rapid Heartbeat, Low Blood Pressure, and Fainting Risk

If you lose intravascular volume, compensatory sympathetic activation produces tachycardia and vasoconstriction but may fail to maintain blood pressure, increasing orthostatic hypotension and syncope risk. You’ll notice a rapid pulse, lightheadedness on standing, and possible brief loss of consciousness; these reflect reduced preload and organ perfusion. Measure heart rate, blood pressure supine and standing, and assess capillary refill and mental status. Management focuses on restoring euvolemia, monitoring hemodynamics, and addressing arrhythmia triggers. Use validated protocols and consider point‑of‑care ultrasound for volume assessment when available. Employ continuous monitoring in unstable patients, titrate fluids to response, avoid excessive crystalloids, and consult critical care for refractory hypotension or recurrent syncope. Immediately evaluate.

| Sign | Clinical implication |

|---|---|

| Tachycardia | Sympathetic compensation |

| Low BP | Reduced perfusion risk |

| Syncope | Immediate evaluation needed |

Who Is Most Vulnerable and Simple Prevention Strategies

Since dehydration most often harms people with impaired thirst, fluid losses, or altered renal handling, you should watch older adults, infants, and those with acute gastroenteritis, fever, or heavy sweating closely. You should also monitor people using diuretics, anticholinergics, or with cognitive impairment; they dehydrate faster and require proactive fluid plans. Simple prevention reduces morbidity: schedule fluids, use oral rehydration solutions during illness, and modify environments to limit heat exposure.

- Schedule regular small-volume intake

- Prefer oral rehydration solutions

- Use wearable or app reminders

Innovate with reminders, wearables, or smart bottles to detect low intake and prompt replacement. If urine output drops or dizziness appears, act immediately—measure weight, check mucous membranes, and seek care when signs progress. Prevention is evidence-based and suited to clinical settings.

Conclusion

You should monitor for early signs—thirst, dry mouth, reduced skin turgor, concentrated urine, tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, dizziness, headache, decreased sweating—and prioritize fluid and electrolyte replacement. Older adults, infants and patients on diuretics are at higher risk, so check supine-to-standing physiologic measurements, urine output and mental status frequently. If hypotension, oliguria or persistent symptoms occur despite rehydration, don’t delay—seek urgent care promptly to prevent end-organ injury. Timely intervention reduces morbidity and hospital admission rates in vulnerable patients.